Revision Strategies

Revision Strategies

Why is Revising Important? What is Revision?

Now what? You’ve done your research, written your paper, but the big question now is: what do you do next? Answer: Revise. Although it can be a daunting word, revision is the time during your writing when you can carefully go back over your paper to fix any mistakes that may confuse or trip up your reader. Revision is a time to smooth out the flow of your thoughts through transitioning between your paragraphs, to make sure that each of your paragraphs are balanced with supporting evidence and your own original thought, and to look at sentence level edits like grammar and sentence flow in the final stages. While most see this as a time to make sure commas are in the right place, revision is for looking at the big picture just as much as the fine details and below are some tips and tricks to get you started!

How do I Go About it?

Time

One of the first steps in the revision process is making sure you set aside enough time to properly edit your paper. If you finish a paper twenty minutes before it’s due, then there is little you can do to revise it. Although sometimes it’s hard to find time to write and revise amidst your busy schedule, I promise it’s worth it!

Writing a paper a few days before it is due will allow you to take a step back and edit the big and small details without the pressure of a looming deadline. This will also give you time to consult writing tutors, your classmates, or your teacher if you find you need help during the process. The ratio of planned writing time to revision is usually along the lines of 70/30 or 80/20 depending on the type of writing assignment you have.

For example, if you are assigned an 8-page research paper, then you are more than likely going to spend 70% of your timing writing and 30% of your time revising since you will have more writing that needs revising before you turn it. This is versus if you are assigned a 1-page reflection essay that requires you to spend more time writing at 80% and only about 20% of your time revising since there is only so much writing that can fit onto one page.

Let’s face it, many of us get bored while writing. Taking a brief moment to step back after writing your first draft to do other things will allow you to return to the assignment later with fresh eyes in order to spot any errors that you may have missed before.

The Big Picture

When thinking about revision, our minds often jump to making sentence-level edits first. However, revision is much more than that!

The first step in any revision process is taking a step back to look at the big picture. Does your paper have an introduction with a thesis statement? Does it have complete and coherent body paragraphs? What about a conclusion that sums up the main focus of your paper for the reader one last time? For a better understanding of how a typical essay is organized, check out “How is it Organized?” on our Reading Strategies page.

Keep in mind that the Big Picture also includes any rubrics or assignment guidelines that your teacher may have given you. It’s important to note requirements like word/paper length during writing and revision as you don’t want to have a complete paper only to realize at the end that you missed the word count or forgot to include three scholarly sources. For more tips on how to keep rubrics and requirements in mind click here to jump to our section on assignment guidelines. Link to rubrics and assignments guidelines sections below.

Main Intent

Start with the main intent of your paper which is found in the ‘thesis statement.’ The thesis statement is included in the introduction paragraph and is typically found at the conclusion of the paragraph. It tells what the text will focus on and how the writer plans to achieve this. Do you state clearly and concisely what your paper will achieve and why and/or how? Do your body paragraphs support your thesis statement? Does your conclusion paragraph match your thesis statement? If you make sure that every part of your paper can be brought back to your thesis statement, then your paper will be more well-rounded and fluent.

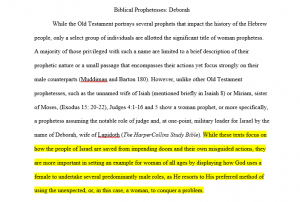

Note the thesis statement that is highlighted in yellow from an analysis paper on the biblical prophetess Deborah below.

This thesis statement tells what the body paragraphs will analyze: “these texts” (analysis being the how). It also tells why: because “they are more important in setting an example for woman of all ages by displaying how God uses a female to undertake several predominantly male roles, as He resorts to His preferred method of using the unexpected, or, in this case, a woman, to conquer a problem.”

The following paragraphs in the paper will analyze the biblical texts that mention Deborah in order to show the reader that God uses women in male roles, an aspect that the writer found while analyzing the texts. We can assume that certain body paragraphs will inform us of the texts and others will attempt to prove the writer’s reasoning with supporting evidence from other sources.

Paragraphs

When reviewing your body paragraphs, you may want to consider why you are writing your paper. Are you trying to argue, persuade, or analyze? Does the structure of your paper enable you to do so? For example, a research paper is different from a persuasive paper since a persuasive paper is trying to persuade the reader to see a topic as the writer does while a research paper focuses on objectively analyzing available sources of a topic to come to a conclusion, without regards to the writer’s personal opinion. So, the persuasive paper will have paragraphs that inform the reader of a topic, but also paragraphs that attempt to prove to the reader why their stance is the best stance on the topic.

Topic Sentences tell the intent and focus of a paragraph. Most of the time they are original thought or observation. They can sometimes be used to attract the reader’s attention to a certain issue or point by giving a preview of what the paragraph is about which propels them to keep reading. Topic sentences are typically found at the beginning and ending of a paragraph to introduce and then sum up the points mentioned within the paragraph.

For example, if you were to write a topic sentence for a paragraph in the aforementioned Deborah essay stating that it is hard to properly analyze the biblical texts because women prophets, especially Deborah, are sadly not as studied as male prophets, a poor intro topic sentence for paragraph might be:

“Many people find it difficult to study the texts with Deborah in them because there is little research done on female prophets.”

While we are able to see that this paragraph will focus on the aspect of female prophets and that it is hard to study the texts with Deborah in them because there is little research on female prophets, there is no transition from the last paragraph to connect the thoughts of the paper nor is the sentence specific about who the “many people” are.

Whereas a more defined topic sentence with proper transitioning between paragraphs and one that introduces the full intent of the paragraph might be:

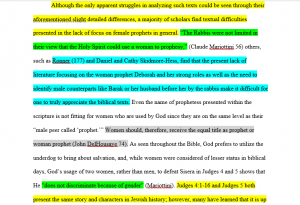

“Although the only apparent struggles in analyzing such texts could be seen through their aforementioned slight detailed differences, a majority of scholars find textual difficulties presented in the lack of focus on female prophets in general.”

This topic sentence, which is the first sentence of the paragraph, transitions the reader from the paragraph before it by using a good transition phrase starting with the word “Although.” “Although” is generally used to compare and contrast ideas, and ere it is used to do just that.

By acknowledging the intent of the paragraph before it as well as previous research in general, this makes the previous information relevant to this paragraph since the content of this paragraph will be slightly contrasting since the writer is stating that this is actually the biggest issue in analysis not the other ones previously stated even though they are important too.

The second half of the sentence also serves to tell the intent of the paragraph. Here as the reader, we know that we are going to be presented with sources that support the idea that there is a lack of focus on female prophets in general which makes it hard to study them.

Some questions to ask might be:

- Do your paragraphs have a clear topic sentence? Do your topic sentences tell the main intent of that specific paragraph? Is it one clear point? If not, you may want to pick the point that best describes the content in your paragraph.

- Do your paragraphs transition smoothly? What draws your attention during reading? Is it to the things that you want to draw attention to?

Examples/Evidence provide a foundation atop which you can build your paper on. Teachers will typically give a minimum or maximum number of sources that you can have in your paper within the rubric or assignment guidelines. Always remember to pick sources that will best support the main intent of your paper and the assignment’s requirements.

However, try to keep an open mind when you’re choosing your sources. When you’re writing a paper, you want sources that will support your argument, but, if you’re struggling to find any, try reconsidering your initial idea. It’s okay to be wrong, and it’s okay to revise and change; that’s all part of the process of learning. What you want to avoid is pulling bits and pieces from sources that don’t agree with your argument. This is called ‘cherry-picking’, and it can actually make writing a paper harder, since you have to construct writing that fits your sources, instead of finding sources that fit your writing.

Some questions to ask would be:

- Do your paragraphs have enough examples, quotes, paraphrasing, and summary from other sources to provide support for the main topic of each paragraph? Do you have more quotes than paraphrasing or vice vera?

- Sometimes it may work better to have a quote rather than summary; however, keep in mind that well-rounded papers typically have an even amount of all in order to keep the audience’s attention and show that you know what you are talking about.

- Do you explain why you included that examples, quotes, paraphrasing, or summary with a follow-up sentence on how it supports your argument or research? Does your inclusion of this example lead into the idea of your next sentence?

- Sometimes having too many sources can drown out your own thought, so be sure to keep an eye out to see if your paragraphs are balanced with original thought and other sources.

One way to check if your paragraphs are complete is by putting them to the PREP test:

Point: Does your paragraph have an introduction topic sentence? What is this paragraph going to be about?

Reason: Does your paragraph give reasoning for your topic sentence? Why do you think this way, or why is your point valid?

Example: Does your paragraph provide an example/ evidence from supporting sources that backup your reasoning. Do you provide quotes, and/or paraphrasing, and/or summary from other sources?

Point: Does your paragraph have a conclusion topic sentence? Does it sum up/(re)state the focus of the paragraph without being repetitive? Does it provide a smooth transition into your next paragraph?

Structural Edits

Structural Edits are just what the name hints at: they involve the overall structure, or layout, of your paper. When doing structural edits, you are looking at how your paragraphs are arranged and how the sentences within them are arranged.

Are your paragraphs arranged in a way that promotes the best flow of thoughts and transitions between them? Are your sentences arranged in a way that enables the reader to follow your thoughts while reading? Or are your paragraphs choppy and jump from idea to idea without any rhyme or reason?

Here are a few different ways of how to go about Structural Edits:

The Outline Method

As you reread your paper, create an outline as you go. Do not look at your original outline but follow the flow of your written paper.

Note where your introduction and thesis are. What does your introduction introduce and how? Note where each of your paragraphs are, what the focus of each paragraph is, what supporting and/or challenging evidence does it provide, and where their topic sentences are. Finally, note where your conclusion is. Does it sum up everything in your paper well?

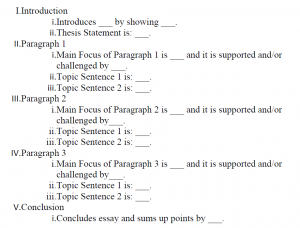

Once you finish, you should have an outline that looks somewhat like this:

(Access a downloadable copy of the Outline Method here.)

Now pull your original outline back out. Does your current outline and original outline match in the same places? If not, look and see how and why. Are your paragraphs in reverse order? Do you have holes in your new outline where you haven’t supported a point in one of your paragraphs? Are your topic sentences in the middle of one of your paragraphs instead of at the beginning or end? Does this work for that particular paragraph (sometimes it can depending on the length and focus of the paragraph)?

Please note that outlines are meant to be flexible, so if your current outline doesn’t 100% match the original outline THIS IS OKAY because some changes are good! As you write and revise, you are usually able to feel and see if it makes more sense to put one paragraph in a different place or to use one source but not the other. Most of the time you know when something doesn’t look or sound right as you’re writing or editing. Just make sure that your new outline matches the main points you are trying to focus on in the original outline. Trust your instincts and, if you are not sure, consult a writing tutor, your classmates, or your teacher for advice on how to revise your paper.

One last thing to remember is the above outline is an outline for a basic essay. If you are doing scientific research or writing a business proposal, your outline is bound to look different. However, the same basic principles still apply. Read your writing, create an outline of your writing from your reading, and consult and compare your original and current outline to see if you need to change anything.

The PowerPoint Method

If you are a visual leaner, one way to help you visualize your paper is by copying and pasting your paragraphs onto PowerPoint slides. Put one paragraph on a slide from beginning to end (ex: Introduction is on the first slide and Conclusion is on the last slide). Now read your paper both in your head or out loud if that helps. Does your paper flow well in the order that it is in? Try moving some of the slides around. Does it read better if Paragraph 2 is in front of Paragraph 1? While you won’t always need to rearrange your paragraphs, if you are finding that your paper is a little hard to read or choppy, using the PowerPoint method can help you see if it is the layout that is affecting your paper’s flow.

Sentences

Note that you could also use the same method when looking at the sentences in one of your paragraphs if it harder to read. Create a PowerPoint and try putting one sentence on each slide. Now seeing if moving some slides around in a different order helps the paragraph to be read better or be understood more easily. Do you find that you need an example to backup up one of your own statements in the paragraph? Do sentences 4 and 5 need to be rearranged to make everything clearer? Do you need to delete a sentence in order for everything to be connected better?

The Paragraph-Cutting Method

If you’re a hands-on learner this might be just the thing for you!

Paragraph cutting is much like the PowerPoint Method. If you’re not comfortable with PowerPoint or don’t have the time, print your paper out and lay it in front of you. With scissors, cut the paragraphs out and line them up top to bottom from introduction to conclusion and start reading.

Just like the PowerPoint method, you can rearrange the paragraphs to see what layout best fits your paper and intent. You can also use this method on individual paragraphs by cutting up the sentences and rearranging them as noted above.

During this time, you might realize that a sentence you have in Paragraph 1 might actually fit better in Paragraph 3, so you can physically cut it out and move it to the other paragraph. Once you are done take a picture of your finished structure just in case you forget your edits later, and then transfer your edits into your actual paper.

The Highlighting Method

The Highlighting Method is a simple way to check the structure of your paper and assess what you do or don’t have in your paper as well. With at least 4 different colored highlighters (or more depending on the type of paper you’re writing or what your rubric asks you to include) highlight the different elements of your paper. Maybe you want your thesis and topic sentences to be highlighted in blue and your supporting evidence to be highlighted in orange. The Highlighting Method gives you a chance to see the placement and type of sentences you have in each paragraph by color-coordinating. This not only helps you to assess your paragraphs but also how much or how little you have in each paragraph.

Note in the example of the Highlighter Method above:

- Topic sentences (which are original thought or observation) are highlighted in yellow.

- Quotes are highlighted in green.

- Summary is highlighted in blue.

- Paraphrasing is highlighted in gray.

- Anything that is not highlighted is original thought from the writer.

The end result: This method allows us to see that this paragraph is balanced with original thought as well as a variety of sources and ways in which the writer was able incorporate them into her paragraph.

Rubrics and Assignment Guidelines

Teachers typically give a rubric or assignment guideline when assigning a paper so make sure to consult it when you start the revision process to remind yourself what you need to include in your paper. They are extremely helpful in making sure that you have all the big bases covered in your writing since they include what the teacher expects to find when reading your paper, such as word length, formatting, number and type of sources, and how clear your points are.

It might be helpful for you to print out a copy of the rubric or assignment guideline for yourself and check off if you meet each of paper’s requirements when revising. If you find that you have the box for word length checked off but don’t have enough sources to meet the minimum for the source requirement, this gives you a chance to find additional sources and incorporate them into your paper before the deadline.

Rubrics and assignment guidelines can be your best friends when you’re revising! Don’t be afraid of using them to your advantage during the revision process!

Sentence Level Edits

While it’s essential to make sure that there are no issues with the overall structure of your paper, you should also look at some of the smaller problems. You can go about tackling some of the sentence-level edits by proofreading your paper.

Proofreading

Proofreading is usually the final step when it comes to revising. This is when you read over your paper specifically to look for any mistakes involving things such as spelling, grammar, and punctuation. Even though revising involves more than just checking your grammar, it’s still important to make sure that your paper is grammatically correct. Having grammatical errors in your paper can not only cause you to lose points on your assignment, but it can also cause your readers to become confused and misunderstand what you’re trying to say.

Before you begin this process, you should doublecheck to make sure that you’ve handled any larger issues first, such as problems with the organization, style or formatting issues, etc. If everything’s correct, then you’re ready to take a look at the grammatical errors. While proofreading may seem like a tedious process, there are a few strategies that may help you.

Proofreading Strategies

Set your work to the side for a little while.

After you’ve spent some time writing and revising a paper, you become very familiar with it. You know what it says, or what it’s supposed to say. However, this familiarity can actually be a hindrance when it comes to trying to proofread. So, after you’ve finished with your major revisions, consider setting your paper to the side for a bit, maybe overnight, or even just for a few hours if you’re short on time. That way, when you come back to it, you’ll have a fresh perspective to begin proofreading with.

Don’t just use Spellcheck.

Spellcheck, or any program like it, is a very useful tool when it comes to proofreading. You should always make sure to use it before turning in an assignment, as it can catch errors that you might not have noticed. However, you should not rely on it. There are certain problems that it can’t catch, or that it may miss, so you should look back over your paper after using Spellcheck on it.

Print out a hard copy.

Printing out a hard copy of your paper has some of the same benefits as setting it aside for a few days. By the time you’ve reached the proofreading stage of revision, you’ll have already become very familiar with your paper, and you’ll have become used to seeing it on a screen. When you print your paper out, you’ll be seeing it in a new format, which can make it easier to spot errors. Also, having a hard copy of your paper gives you the opportunity to mark-up a physical copy of your work.

Read your work out loud.

Reading your work out loud can help you find grammatical errors, but it’s mainly useful for making sure that your sentences flow together and don’t sound awkward. Something that looks good on paper may actually end up sounding disjointed. This is a great way to ensure that your writing is cohesive. Reading aloud in front of a friend or family member can also be helpful for identifying these types of errors. They may be able to catch things that you may not notice.

Look for one type of error at a time.

Proofreading may seem like a daunting task, as it encompasses so many things. A way to make it less intimidating can be that you only focus on looking for one type of error at a time. For example, on your first read-through, you look for any spelling errors. Then, on your second read-through, you look for any comma errors. This can help to make the proofreading process a little more manageable.

Ask another person to review it.

Once you’re finished proofreading your paper, it can still be helpful to have another set of eyes look over it. Like with setting your work aside, or printing out a hard copy, having a fresh perspective look over the paper can be helpful. You can ask a friend or family member to read your work, or you can always make an appointment with a consultant at the Writing Center to go over your paper. If you’d like to set up an appointment with a consultant, click here.

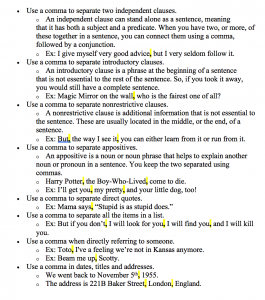

Commas

Many people have trouble knowing when and where to use a comma in their sentences. This can lead to confusion in their readers, because, depending on where a comma is placed, it can change the meaning of the sentence completely. Below are a few general rules that can help you check and make sure that your paper uses commas correctly.

If you still need some help with this, click here for some more examples of proper comma use.

Subject Verb Agreement

Another common mistake that people make while writing a paper is that, in their sentences, their subjects and verbs don’t agree. Subjects and verbs agree when they are both singular or plural, and in the same “person” (first person, third person, etc.). An example of subject-verb agreement would be: “I am” or “he is”, while an example of subject-verb disagreement would be: “He am” or “I is”.

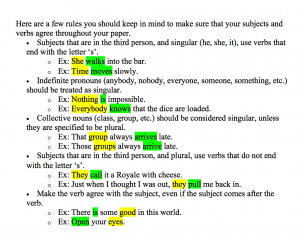

Here are a few rules you should keep in mind to make sure that your subjects and verbs agree throughout your paper.

If you still need some help with this, click here for some more examples of subject-verb agreement.

Active and Passive Voice

While you’re working on your paper, you should always make sure to keep your writing in the active voice, and not the passive voice. The difference between the two is that in the active voice, the subject of your sentence is performing the action, while in the passive voice, the subject is receiving the action. That may sound confusing, so here’s an example to show you what they both look like.

Active Voice Example: The hero saved the day.

Passive Voice Example: The day was saved by the hero.

In the first example, the subject of the sentence, the hero, is performing the verb. He is actively saving the day. However, in the second example, the action already happened. It’s in the past; the day was saved.

In your writing, you want to avoid phrases that sound like the second example. The active voice is typically clearer, which makes it easier for your readers to understand what it is that you’re trying to say.

While you’re editing your writing, if you come across a sentence that includes a “by the…” phrase, that sentence is probably written in the passive voice. You can fix it by rearranging some of your words.

For example: The knight was kidnapped by the dragon.

You see we have a “by the” phrase. That means that this sentence is written in the passive voice, so, what we need to do is reorganize. Who is actually doing something in this sentence? The dragon, he is actively kidnapping the knight. The knight is being useless and doing nothing, so why should he be the star of the sentence? He shouldn’t be; the dragon should be the subject instead. So, he and the knight switch places. If the dragon is the new subject, then we need to update our verb as well.

So, our new sentence would be: The dragon kidnapped the knight.

This sentence is written in the active voice, because the subject of the sentence, the dragon, is the one who is doing something.

If you still need some help with this, click here for some more examples of how to change passive voice sentences into active voice.

Questions to Keep You on Track

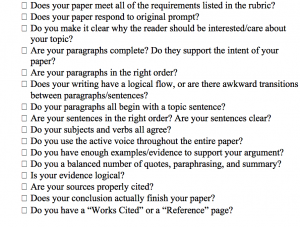

As you’re revising your paper, feel free to use the questions below to help you through the revision process.

Print out your own checklist here.

References

Academic Guides. (n.d.). Writing a Paper: Proofreading. https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/writingprocess/proofreading.

Hobart and William Smith Colleges. (n.d.). Academics: Revision Strategies. https://www.hws.edu/academics/ctl/writes_revision.aspx.

Lumen. (n.d.). Guide to Writing. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/styleguide/chapter/subject-verb-agreement/.

Purdue Writing Lab. (n.d.). Changing Passive to Active Voice // Purdue Writing Lab. Purdue Writing Lab. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/active_and_passive_voice/changing_passive_to_active_voice.html.

Student Success. (n.d.). Commas (Eight Basic Uses). https://www.iue.edu/student-success/coursework/commas.html.

The Writing Center. (n.d.). Subject-Verb Agreement. https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/guides/subject-verb-agreement.